|

|

||

|

Pro Tools

FILMFESTIVALS | 24/7 world wide coverageWelcome ! Enjoy the best of both worlds: Film & Festival News, exploring the best of the film festivals community. Launched in 1995, relentlessly connecting films to festivals, documenting and promoting festivals worldwide. We are sorry for this ongoing disruption. We are working on it. Please Do Not Publish until this message disappears. For collaboration, editorial contributions, or publicity, please send us an email here. User login |

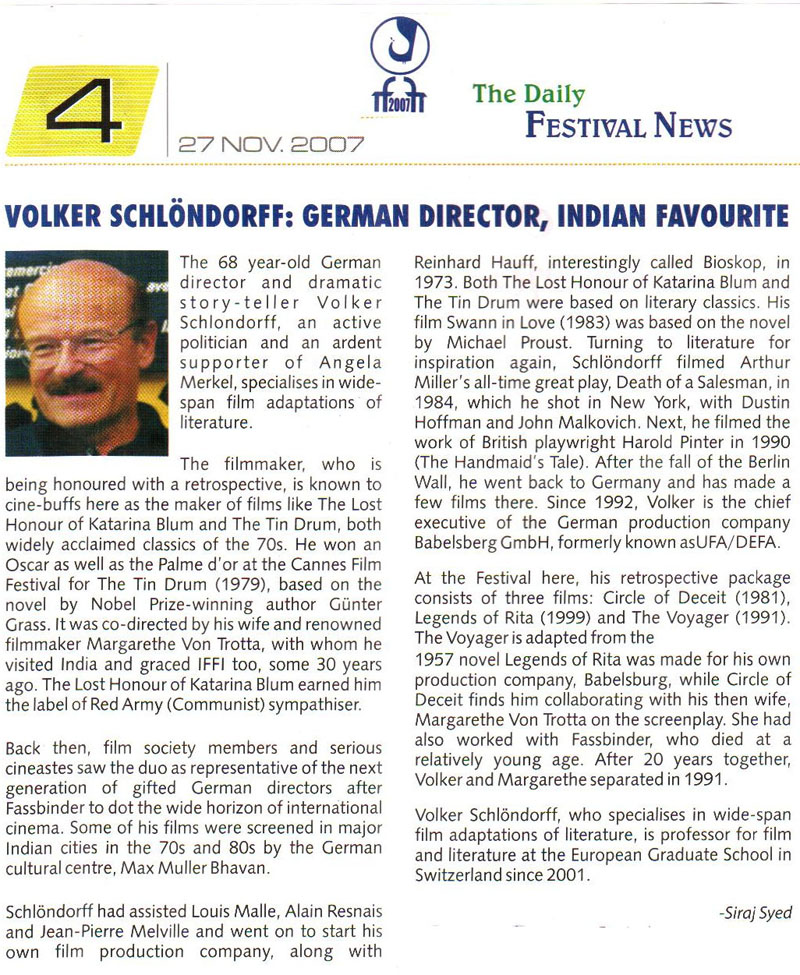

Siraj SyedSiraj Syed is the India Correspondent for FilmFestivals.com and a member of FIPRESCI, the International Federation of Film Critics. He is a Film Festival Correspondent since 1976, Film-critic since 1969 and a Feature-writer since 1970. He is also an acting and dialogue coach. @SirajHSyed  Rang Rasiya/Colours of Passion, Review: ‘Playboy’ painter and the pin-up prostitute Rang Rasiya/Colours of Passion, Review: ‘Playboy’ painter and the pin-up prostitute At last, the much-talked about and mired in censorship issues, director Ketan Mehta’s Rang Rasiya/Colours of Passion finds release in India, with a For Adults Only certificate. There was similar controversy with his 1993 Maya Memsaab, based on Flaubert’s 19th century novel Madame Bovary, and starring ShahRukh Khan opposite Mehta’s wife Deepa Sahi. Twenty years ago, it was exposed female (and some male) anatomy that raised many eyebrows. Curiously, Raja Ravi Varma, the original Rang Rasiya of the title, was a poet who painted his muse semi-nude and faced the wrath of religious fundamentalists, who wanted to censor his art. The film, made 100 years after his death, faced the censorship mores of the same nation. Twenty years later, it is Ketan Mehta again, in the same scenario, only the earlier film was fiction while this is a fictionalised biopic. Raja Ravi Varma’s grand-daughter found that the film was “fraudulently claiming to be based on Raja Ravi Varma’s life. She wanted to stop the release of the film, days before it was to reach there. She said, “It is highly derogatory as it picturises Hon’ble Raja Ravi Varma as a playboy.” Following this, the Prime Minister’s Office asked the Information and Broadcasting Ministry to look into the matter. The ministry found that the movie had been cleared by Central Board of Film Certification with an ‘A’ certificate five years ago, and that its release had got delayed because of distribution-related issues. Realising that there were no reasonable grounds to either “recall” the movie or force a re-release, with more deletions, the ministry declined to intervene. And so we get to see Rang Rasiya. I saw it at a Mumbai single-screen cinema, one that can seat 1,100, along with, maybe, 29 others. (There had been a regular press preview, but, like in the case of most Hindi films, I was not invited. Wonder what have I done in my 45 years as a Hindi critic to now be branded an English film critic? I have always been reviewing Hindi films). An audience of 30 in a single screen cinema on a Saturday evening show, the day after its release, augurs badly for any film. So much for the box-office prospects of Rang Rasiya! Now for the story. This is the story of a little boy who grew up making charcoal sketches on freshly whitewashed temple walls, and went on to earn the title ‘Raja’ in the Thiruvananthapuram court, Kerala, for his artistic prowess. His painting of a ‘low-caste’ woman, who worked in his wife’s palace, brought him wrath and recognition alike. He soon moved from Kerala to Baroda to Bombay. Varma’s deep involvement with Sugandha, the Maharashtrian prostitute who became Menaka, Damayanti and Urvashi in his most acclaimed works, caught the fancy of many critics and admirers. He was accused of remaking gods in the image of men, and insulting them by portraying them in the nude. He countered that he saw divinity in both gods and humans, and that nudity was the purest form he knew. After his last commercial release, Mangal Pandey: The Rising (2005), a film about nationalist soldiers’ uprising against the colonial British forces, Mehta chose to make this film because “Varma was the most fascinating artist of that era” and his character, persona and paintings fascinated Mehta’s from his days as a student of film direction at the Film and Television Institute of India. After reading Desai's novel, he formulated the script of his new film, along with Sanjeev Dutta and Sitanshu Yashashchandra. Now what is it about the 19th century that prompted Mehta to makeas many as three films positioned in that epoch? A biopic would have needed to capture the soul of the painter, whereas a biographical novel has all the licence to touch-up and colour the real story. With no ready-reckoner references at hand, one can only guess how much was imagined by Ranjit Desai, the novelist, and what has been added or subtracted by M/s Mehta, Dutta and Yashashchandra. What comes across in this broad-canvassed tale is a narrative that has jumps in time, geography, tone and tenor. In the film, Varma is painted as a tall, attractive man, with a toned, sculpted physique, who is first the object of desire among women and then turns indulgent and a libertine himself. Neither is effectively treated. There is almost nothing of his lineage and childhood, though, from all accounts, they were key elements in the moulding of his persona. To create the 19th century ambience, Mehta often resorts to dark, translucent hues covering popular landmarks. Dialogue is largely apt, except for the numerous court scenes, and the outburst by Sugandha towards the end, both falling flat. Varma’s egotistical dismissal of Sugandha’s being appears baseless and contrived, not to say illogical. In some scenes, all ambient sounds go silent and only one character speaks, softly, without any visible reason. On many occasions, you get the distinct feeling that the 132 minute long film has been trimmed by 20-30 minutes, and not only to make it censor-safe, but perhaps, to try and retain audience interest. As a consequence, the film is never utterly boring, but in the process, some of the roles have been shortened or deleted altogether, and some shots/scenes have suffered the same fate. On the plus side, colours are a feast for the eyes, as they should be, in a film like this. Nitin Chandrakant Desai’s production design and Niharika Khan’s costumes are above par. Sandesh Shandilya’s music is generally mood-enhancing, especially in the songs. Singers Roop Kumar Rathod, Sonu Nigam, Kailash Kher, Sunidhi Chauhan, Anwar Khan and Keerthi Sagathia have all done a good job. The sufi touch, although well blended in the song, seems out of context. Rhythm-wise, one wishes the drums weren’t so loud and the beat less frenetic. Randeep Hooda, who was steely dark and natural as the Messenger of Death in The Coffin-Maker, is a little awkward here, one of his earliest films, and delivers his lines as if under some kind of light intoxication, and walks as if suggesting a limp or a sprain. Was he told to suggest addiction? He is shown smoking some narcotic and participating in orgies, so it would not be too shocking to see him sway a bit almost all the time. But without getting any hint, one wonders. Moreover, his generally deadpan persona suits cold-blooded characters, like in The Coffin Maker and Highway. Mehta cast him after seeing him D and Risk. He proves no risk here, while offering limited dividend. What could have been a great opportunity pans out as just above par effort. Nine years younger than Nandana, he manages to keep his stage presence in the key scenes and gets tp act-out a whole gamut of emotions. Nandana Sen (daughter of Nobel laureate Amartya Sen) trained at the Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute, New York, as well as the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, London. Her films include Black, Tango Charlie and My Wife's Murder. She half-jokingly calls Sugandha “...the first pin-up girl, in Indian art!” Acting-wise, she too, like Randeep, is unable to match the demanding requirements, and her peep-show too is sensual without being earth-shaking. There is little question that she has unconventionally attractive looks, and is bold and uninhibited. It is in the dramatic moments that her limited prowess shows. And her diction, like that of most women in the film, is, strangely, Westernised. Part of the blame must go to the script, which does not allow her much characterisation. No, I am not saying she is bad, far from it. But, like it is for Hooda, more was expected in a role offering as golden an opportunity as this. Was her willingness to do a Zeenat Aman (Satyam Shivam Sundaram) or a Mandakini (Ram Teri Ganga Maili), in terms of uncovering mammary gland(s) for the camera, a deciding factor in the casting? Paresh Rawal shows that bereft of over-acting or hamming, he is an even better actor. Rajat Kapoor, Tom Alter and Suhasini Mulay are wasted in inconsequential parts, though Tom has some footage as an English judge. Vipin Sharma, Sachin Khedekar, Shrivallabh Vyas and Ashish Vidyarthi try to enliven their brief roles. Darshan Jariwala is a bit stagey, as the religious opponent of Varma, but that is not too far from the brief. Vikram Gokhale underplays the prosecutor, with only occasional modulations, thereby flattening the performance. Rashaana Shah is a comely Kamini, the seductress and Varma’s first model. Since the story is narrated by Ravi’s brother Raj as an audio flashback, it is disappointing to see Gaurav Dwivedi get a raw deal on screen. Rang Rasiya is the kind of film you can see, reflect upon for a moment or two in the cinema foyer, and then go back to the real world. In the process, you might discover that the father of Indian cinema, D.G. Phalke, was an apprentice at Varma’s printing press and feel the wiser for this piece of general knowledge. As for 'one for the road' nudity, it was a major issue way back in 1890. It might have been a minor issue ten years ago, when work on the film began, but in 2014, it is a non-issue. To patrons of art and of good cinema, it is a trifling detail. To the wolf-whistling and sexually deprived/depraved class of viewers, it is 'half' baked much ado about nothing. Rating: **1/2 Trailer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_TC8o690ns0 The real Raja Ravi Varma India’s most celebrated painter. As controversial as he was gifted, Ravi Varma moved the Hindu gods and goddesses out of temples and into the common man’s home, and immortalised many people and moments in history through his brushstrokes. Deeply influenced by European art, Varma won many international contests and was honoured by many princely states in the country. Ravi’s mother, Uma Amba Bai Tampuratti, was a poet, his father, Ezhymavil Neelakantan, Bhattathiripad, was a Sanskrit scholar and his uncle, Raja Raja Varma, was an amateur artist who taught young Ravi his initial art lessons. As a little boy, Ravi Verma used to draw and colour the walls of his home with pictures of characters found in everyday life. At the age of 14, Ayilyam Thirunal Maharaja took him to Travancore Palace, and he was taught water painting by the palace painter, Ramaswami Naicker. After 3 years, Theodore Jenson, a Dutch/British painter, taught him oil painting. Once he decided to take up painting as a profession, he went on foot to Mookambika temple in South Canara district of Karnataka, to worship the goddess there, and make an auspicious beginning. His first professional painting was a portrait of a family in Calicut, and he received the first paid commission. His paintings later on became so popular that keeping any of his works at homes and palaces came to be considered a matter of status symbol. He also became internationally acclaimed when he won the first prize in the Vienna Art Exhibition in 1873. Most of his oil paintings are based on Hindu epic stories and characters. In 1873 he won the First Prize at the Madras Painting Exhibition. He was also India’s first ever calendar artist. Ranjit Desai, author of the biographical novel Ranjit Desai (1928-92) was born in Kolhapur district, Maharashtra. Biographical novels were his forté. His most famous works are Morpankhi Sawalya, Shriman Yogi and Swami, based on the life of Madhavrao, the third Peshwa (Maharashtrian royal). He won the Maharashtra Rajya (state) Award (1963), Hari Narayan Apte Award (1963), the Sahitya Akademi Award (1964) and the PadmaShri, from the Government of India (1973). 08.11.2014 | Siraj Syed's blog Cat. : 19th century Deepa Sahi Ketan Mehta Madame Bovary Nandana Sen Paresh Rawal Phalke Raja Ravi Varma Randeep Hooda Rang Rasiya Independent

|

LinksThe Bulletin Board > The Bulletin Board Blog Following News Interview with EFM (Berlin) Director

Interview with IFTA Chairman (AFM)

Interview with Cannes Marche du Film Director

Filmfestivals.com dailies live coverage from > Live from India

Useful links for the indies: > Big files transfer

+ SUBSCRIBE to the weekly Newsletter DealsUser imagesAbout Siraj Syed Syed Siraj Syed Siraj (Siraj Associates) Siraj Syed is a film-critic since 1970 and a Former President of the Freelance Film Journalists' Combine of India.He is the India Correspondent of FilmFestivals.com and a member of FIPRESCI, the international Federation of Film Critics, Munich, GermanySiraj Syed has contributed over 1,015 articles on cinema, international film festivals, conventions, exhibitions, etc., most recently, at IFFI (Goa), MIFF (Mumbai), MFF/MAMI (Mumbai) and CommunicAsia (Singapore). He often edits film festival daily bulletins.He is also an actor and a dubbing artiste. Further, he has been teaching media, acting and dubbing at over 30 institutes in India and Singapore, since 1984.View my profile Send me a message The Editor |